Special thanks to @tombh for proofing this blog post!

Edit 5/28: added a link to the repo and corrected the solver I used

Did you know that LinkedIn has games? I sure as hell didn’t until my Dad showed me that they in fact have 5 (!) different games that you can play.

One of them stood out to me as somewhat interesting, Queens:

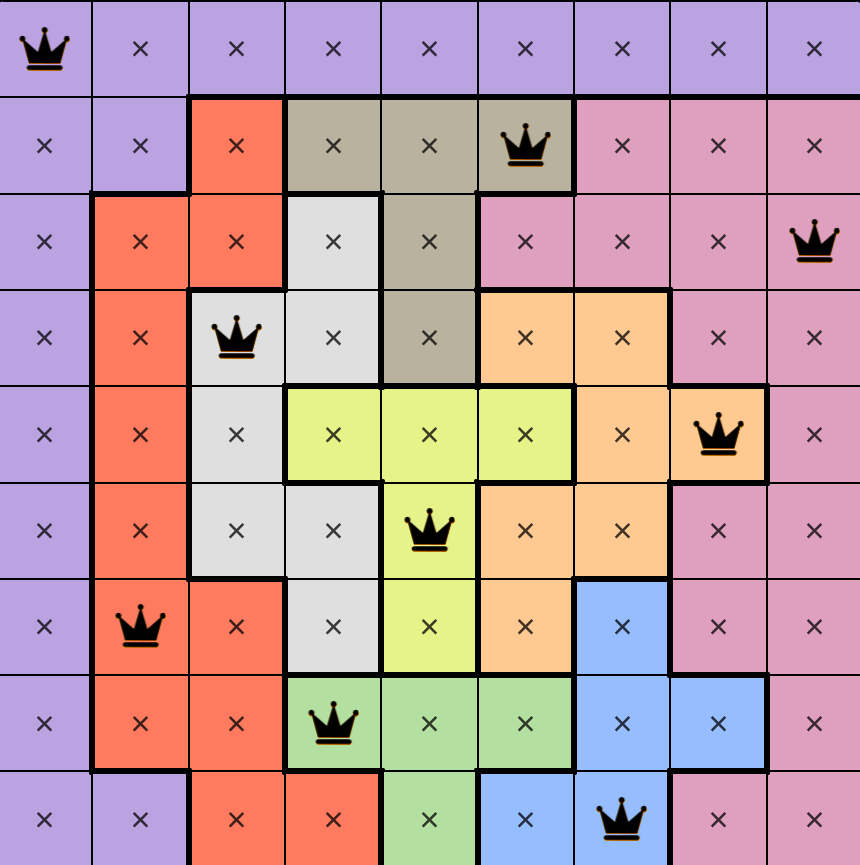

Solved Queens board

Solved Queens board

Queens looks a lot like the classic logic problem, N-Queens (a generalized version of 8-Queens). N-Queens asks “given an NxN board, can you place N queens such that no queen shares the same row, column, or diagonal (which is how a queen moves in chess)?”

N-Queens is impossible for \(N \leq 3\), and for any greater N it can be solved via a backtracking algorithm which places one queen at a time, “backtracking” to a valid partial solution each time it encounters an invalidly placed queen. This lets the algorithm cut out large swaths of the search space.

That’s cool and all when you are prepping for Leetcode interviews, but I’m not solving Leetcode problems. But I am looking to get better at reducing problems to SAT.

Good material for a blog post isn’t enough (I’m vain), so I’ve built a Firefox extension that will play my solution so I can own my Dad and all those CEOs the game keeps comparing me to.

Quick SAT Rundown

For the uninitiated, SAT is a classic computer science problem known to be NP-complete.

The core of the problem is finding boolean values for a given formula - which are built by using logical operations of and (\(\land\)), not (\(\neg\)), and or (\(\lor\)) - such that the formula returns true.

A provably correct solver will have to try all possible boolean values for the formula, of which there are \(2^n\) with \(n\) being the number of variables in the formula. Now-a-days, solvers use pretty fancy algorithms to section off large parts of the search space so hopefully it doesn’t have to actually try that many.

Many problems can be turned into “decision” problems (a yes or no) which also happens to correspond pretty well to SAT problems. Today I’m faced with one of those decision problems.

Now on with the show.

N-Queens SAT Reduction

To turn N-Queens into a SAT problem, we need to figure out what we’re asking the SAT solver a “yes” or “no” question about. In my case, I want to ask it ~81 (9x9) questions each being: “is there a queen placed at square (row, column)”

To do this means we’ll introduce NxN variables into the formula, one for each square/cell.

For each given cell, there are three different types of constraints on it:

- It must be the only element that is true on the entire row

- It must be the only element that is true on the entire column

- It must be the only element that is true on its two different diagonals

My initial attempt to encode this was to write a formula for each cell describing all the cells it was not, thinking that somehow this would magically end up in a satisfiable formula.

So, in this case we would say for a given cell:

- if a queen is placed on a cell then it implies everything else on its row is false

- if a queen is placed on a cell then it implies everything else on its column is false

- if a queen is placed on a cell then it implies everything else on its diagonals are false.

This, however, is naive and generates quite a few formulas. Using the above constraints it also doesn’t require that any are set. This means all cells being set to false (or no queen placed there) will satisfy the formula (making the solver’s job very easy).

Cheating (myself)

After my initial attempt and confusion, I stumbled on a PowerPoint™ lecture about reducing N-Queens to SAT that was quite helpful and showed where my approach was failing.

Instead of going cell, by cell, it is a bit easier to model the problem row-by-row, column-by-column, and diagonal-by-diagonal.

It also showed where my approach went wrong: generating an overly verbose boolean formula for the row and column at each cell to contain “at most one” variable that is true, but not to contain “exactly one” that is true.

Thankfully, “at most one” is on the way to “exactly one.” If we had “exactly one,” it also must be the case that there be “at most one.” What are we missing? “At least one.” If we have “at least one” and “at most one,” then we end up with “exactly one.” “At least one” is also very easy! It is just an or (\(\lor\)) of all the cells.

With this knowledge we can build a helper function \(exactlyOne\) and use it for each row and column: $$ exactlyOne(\{…\}) = atMostOne(\{…\}) \wedge atLeastOne(\{…\}) $$

Where \(atLeastOne\) is all the elements (in the row, or column) or’ed \(\lor\), but \(atMostOne\) is a bit more complicated:

$$ atMostOne(terms) = \bigwedge\limits_{i=0}^{N-1} (terms_{i} \implies (\bigwedge\limits_{j=i+1}^N \neg terms_{j})) $$

or if you’re not a programmer who thinks about \(\bigwedge\) like a loop: $$ atMostOne(terms) = \bigwedge\limits_{0 \leq i<j \leq n} terms_i \implies \neg terms_j $$

For each item in \(terms\), it is implied that it is not any of the following terms.

An Aside

This initially confused me as my first idea was that “given a cell, it implies all the cells in its group (row, column) are false”. This would require the inner \(\bigwedge\) to be bounded via \(j=0, j\neq i\) so that it gets all the other items of the group. You can get a good feel for why the above is more optimal though if you write it out when \(n=2\): $$ (term_i \implies (\neg term_{i+1})) \land (term_{i+1} \implies (\neg term_i)) $$

Oops! The right-hand side of the \(\land\) is just the contrapositive, so you’re and’ing (\(\land\)) a duplicate condition. A better way of seeing it is when you use a logical interpretation such as in the N-Queens Lecture.

There, the multiple contrapositives will show up as duplicate pairs of \(\lor\)s that look like: $$ (\neg term_i \lor \neg term_j) \land (\neg term_j \lor \neg term_i) $$

Which is why the inner loop’s bound starts at the next item in the list, as to not duplicate the effort of the previous iteration by generating duplicate pairs.

Back to It

This helpful function can aid us in formulating the constraints for rows and columns since it is guaranteed that a queen must be on every row and every column. However, it is not guaranteed that every diagonal must have a queen, just that two queens should not share a diagonal.

For example:

. . Q X

Q . X .

. X . Q

X Q . .

Notice that the diagonal denoted with X’s does not have a queen. This is a gotcha we’ll see in a moment, but the easy way to solve this with another existing function we have is the \(atMostOne\) constraint. It is true that there must only be \(atMostOne\) queen per diagonal.

Now that we have all the building blocks, we can build the final formula: $$ rowConstraint = \bigwedge\limits_{i=0}^N exactlyOne(row_{i}) \newline columnConstraint = \bigwedge\limits_{i=0}^N exactlyOne(column_{i}) \newline diagonalConstraint = \bigwedge\limits_{i=0}^{numDiagonal} atMostOne(diagonal_{i}) \newline NQueens = rowConstraint \wedge columnConstraint \wedge diagonalConstraint $$

Queens

So, now that we’ve solved N-Queens, LinkedIn’s Queens should be very similar, but the approach needs to be adapted to the new rules. The rules for this version is as follows:

- There must be one queen per row

- There must be one queen per column

- There must be one queen per color

- No queen can be adjacent to another

So we’ve added the constraint of color but dropped the constraint that the queens couldn’t be on the same diagonal. The only diagonal that we’re worried about is the one that is directly adjacent.

Armed with our helper of \(exactlyOne\) in hand, we can start to get a foothold on the problem: $$ rowConstraint = \bigwedge\limits_{i=0}^N exactlyOne(row_{i}) \newline columnConstraint = \bigwedge\limits_{i=0}^N exactlyOne(column_{i}) \newline colorConstraint = \bigwedge\limits_{i=0}^{numColors} exactlyOne(colors_{i}) \newline $$

Now all we have left is to deal with adjacency. What is adjacency? In Queen’s context we can’t have a queen placed on the same color, nor can they be placed on the same row or column. What does that leave us with?

Well, it only leaves us with the adjacent diagonal of every cell that borders a different color. I will call this an “edge” For example:

X X . .

X Y . .

. . . .

. . . .

In this case, the only adjacency we’d be worried about with colors X and Y is the diagonally adjacent (0, 0) -> (1,1). Since the number of edges with such a diagonal is small, we can just iterate over every cell on the board, look at its diagonal neighbors, and if they aren’t the same color then we will add them to a set for the cell.

The pseudo-code would be something like:

Pair = Tuple[int, int]

def get_diagonal_neighbors(i: int, j: int, n: int) -> List[Pair]

def get_edges(grid: List[List[Pair]]) -> Dict[Pair, Set[Pair]]:

result = {}

for i in range(len(grid)):

for j in range(len(row)):

# get diagonal neighbors that are different than the current cell

for (dx, dy) in get_diagonal_neighbors(i, j):

if grid[i][j] != grid[dx][dy]:

# add them to the set

result[(i, j)] = set(result[(i, j)] | {(dx, dy)})

return result

Now that we have a dictionary full of edges which correspond to their “adjacent” neighbors, we need to figure out how to constrain them.

Without much thinking, I initially pulled out \(exactlyOne\). However, in doing so, you make it so that the solution must contain a queen in one of the spots that have an adjacency. This will work for a very small subset of Queens games (which I found out the hard way).

Instead, like diagonals in N-Queens, we just need to make sure that there is \(atMostOne\) item in the adjacent grouping.

Because I’m lazy, the above code isn’t particularly careful about generating duplicate \(atMostOne\) constraints.

Using the previous example, both (0, 0) -> {(1,1)} and (1,1) -> {(0,0)} would be in result, meaning that

an implication will get generated both ways.

Since SAT solvers are super smart about this sort of thing, it isn’t hindering anything, but is left as an exercise for the reader to actually optimize this.

Now that we have all the pieces, lets formalize it: $$ …\newline adjacentConstraint = \bigwedge\limits_{i=0}^{numAdjacent} atLeastOne(adjacent_i) \newline Queens = rowConstraint \wedge columnConstraint \wedge \newline colorConstraint \wedge adjacentConstraint $$

Going for Gold

After proving to myself that this worked via manually inputting Queens games, it was time to put it to the test: getting the world record on LinkedIn’s Queens. SAT solvers are slow in the worst case, but it turns out that most problems aren’t the worst case and CVC5 solves this blazingly fast.

It took some work to get a Firefox extension up and running with a small Python API to ferry the puzzle/solution to and from CVC5 (wish I could say it was using Z3-wasm, but I had many issues), and I had it working.

And I’m proud to report, that it did it 🎉

I have become the conduit through which CVC5 has proven itself smarter than 99% of CEOs and 99% of my fellow University of Utah alums.